Today's post comes from the book Off-Camera Flash : Creative Techniques for Digital Photographers by Rod and Robin Deutschmann. It is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.

Today's post comes from the book Off-Camera Flash : Creative Techniques for Digital Photographers by Rod and Robin Deutschmann. It is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.Capturing motion with your off-camera flash opens a world that is seldom seen. Being creative means pushing your vision and your equipment further than ever before.

VARIATIONS ON A THEME

As an artist with an off-camera flash, you have more options than most when it comes to dealing with movement. A quick splash of light from any angle or height will freeze things when nothing else will. It will also clear up a poorly executed pan or fill in the shadows on quickly moving subjects. You can, as always, highlight any tier of graphic information. Plus, if you use a fast enough shutter speed, you can darken even the brightest sky, ensuring that you can keep your true intent illuminated above everything else.

STARTING WITH ONE FLASH

As always, if you’re new to all this, begin with one flash connected to your camera via a wire and try to freeze some action. It doesn’t matter what—just freeze something. Even at slower shutter speeds, the flash will help freeze movement. Keep adjusting the power output on the flash. Change the aperture in the camera. Move closer and further away. Review your images. Notice

how even the slightest changes can weaken or strengthen the flash. Now, modify the light. Use a softbox to enlarge it or a snoot to direct it. Get to know the magic that one flash offers before you move onto more.

ADDING MORE LIGHT

When your skill allows it, move onto two flashes and trigger them wirelessly. Once you’ve mastered this, move onto three flashes—and then even more. Be creative with your lighting setups, triggering methods, and modification rituals. Don’t keep doing the same thing each time you shoot. Explore the possibilities of motion frozen with flash while paying attention to how things change in the rest of the image. You will use all of this experience later.

Two unmodified flashes gave this image the needed boost of light it deserved. The flashes were set off with the help of two optical slave devices called “peanuts.” These extremely small optical receivers are connected to a PC wire that runs directly to each flash. When these “peanuts” sense a bright contrast, they set off the flash unit they are connected to. In this case, the camera’s pop-up flash provided the needed contrast. When the pop-up flash fired, so did the other flashes. The pop-up flash did not illuminate any portion of the scene; it was only used as a triggering device for the much more powerful off-camera flashes

Two unmodified flashes gave this image the needed boost of light it deserved. The flashes were set off with the help of two optical slave devices called “peanuts.” These extremely small optical receivers are connected to a PC wire that runs directly to each flash. When these “peanuts” sense a bright contrast, they set off the flash unit they are connected to. In this case, the camera’s pop-up flash provided the needed contrast. When the pop-up flash fired, so did the other flashes. The pop-up flash did not illuminate any portion of the scene; it was only used as a triggering device for the much more powerful off-camera flashes

You have three choices when dealing with motion and using an off-camera flash: freeze it, let it blur, or do both at the same time. Here, one hand-held flash brings our message into the light (above).

It’s amazing what your images can look like when you employ as many lights as you possibly can. Remember: the more power you have, the more options you gain.

Seven unmodified lights set to full power were employed to freeze the twirling model. Four were used behind an umbrella, two were set on light-stands, and one was hand held by an assistant (and sometimes the photographer). High contrast and saturation settings were used along with a bluer-than-normal white balance.

Seven unmodified lights set to full power were employed to freeze the twirling model. Four were used behind an umbrella, two were set on light-stands, and one was hand held by an assistant (and sometimes the photographer). High contrast and saturation settings were used along with a bluer-than-normal white balance.

One off-camera, unmodified flash can still be quite effective in freezing detail. The shallow depth of field seen here was accomplished with a very fast 85mm lens (f/1.4). The longer focal length also allowed the photographer to move backward, dramatically changing the offered perspective.

One off-camera, unmodified flash can still be quite effective in freezing detail. The shallow depth of field seen here was accomplished with a very fast 85mm lens (f/1.4). The longer focal length also allowed the photographer to move backward, dramatically changing the offered perspective.

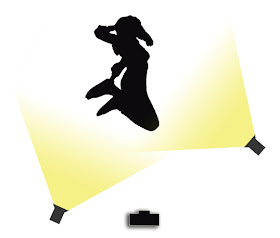

Two unmodified lights perfectly illuminated the right and front side of our model. A verywide-angle lens (18mm) was used.

Two unmodified lights perfectly illuminated the right and front side of our model. A verywide-angle lens (18mm) was used.

Four unmodified flashes set to full power were needed to light each corner of our model during this rather dramatic jump over the San Diego skyline. A very light red filter was added to each flash to complement the redder-than-usual white balance setting. In-camera contrast, saturation, and hue choices were adjusted to taste. A smaller aperture (f/11) and shorter focal length lens (18mm) were used to help with the required depth of field.

Four unmodified flashes set to full power were needed to light each corner of our model during this rather dramatic jump over the San Diego skyline. A very light red filter was added to each flash to complement the redder-than-usual white balance setting. In-camera contrast, saturation, and hue choices were adjusted to taste. A smaller aperture (f/11) and shorter focal length lens (18mm) were used to help with the required depth of field. Now, increase the power of your flashes by combining them. Create as much light as possible and see what happens. Overpower the sun itself if you can. Know what gear it takes to have complete control over every aspect of the scene. And don’t limit your vision when it comes to subjects, either; there are more things to shoot than just people, so try it on moving animals, as well. Understand the maximum amount of light you can produce with all your gear, then figure out how you can use it with all moving subjects—at any time of the day or night.

No comments:

Post a Comment