Today's post comes from the book The Best of Portrait Photography, 2nd Edition by Bill Hurter. It is available at Amazon.com and from other fine retailers.

Today's post comes from the book The Best of Portrait Photography, 2nd Edition by Bill Hurter. It is available at Amazon.com and from other fine retailers.At the heart of any great portrait photographer’s body of work is a complete and thorough understanding of the traditional rules of posing. While it has become fashionable to break these, the true hallmark of finesse is knowing which rules to break and when.

In any discussion of subject posing, the two critical elements are that the pose appear natural and that the person’s features be undistorted. If the pose is natural and the features look normal, then you have achieved your goal and the portrait will be pleasing to you and the subject. While every rule of posing could not possibly be followed in every portrait, these rules exist to provide a framework for portraying the human form naturally, attractively, and without distortion.

The Hands

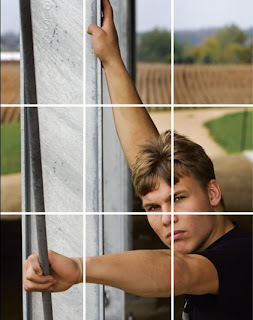

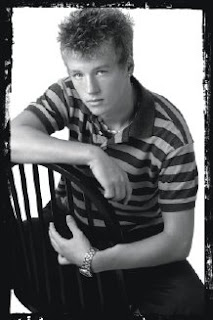

Posing hands properly can be very difficult because, in most portraits, they are closer to the camera than the subject’s head. Thus, they appear larger. One thing that will give hands a more natural perspective is to use a longer-than-normal lens. Although holding the focus of both hands and face is more difficult with a longer focal length, the size relationship between them will appear more natural. Additionally, if the hands are slightly out of focus, it is not as crucial as when the eyes or face are soft.

One basic rule is never to photograph a subject’s hands pointing straight into the camera lens. This distorts the size and shape of the hands. Always have the hands at an angle to the lens. Another basic is to photograph the outer edge of the hand whenever possible. This gives a natural, flowing line to the hand and eliminates the distortion that occurs when the hand is photographed from the top or head-on.

The following suggestions give you a few additional elements to keep in mind as you pose your subjects’ hands.

1. Always try to “break” the wrist. This means raising the wrist slightly so there is a smooth bend and gently curving line where the wrist and hand join.

2. Always try to photograph the fingers with a slight separation in between them. This gives the fingers form and definition. When the fingers are close together, they look like a two-dimensional blob.

3. When photographing a man’s closed hand, give him something small (like a pen cap), to wrap his fingers around. This gives roundness and dimension to the hand so that it doesn’t become a clenched fist.

4. As generalizations go, it is important that the hands of a woman have grace, and the hands of a man have strength.

Hands in Group Portraits. Hands can be a problem in small groups. Despite their small size, they attract attention to themselves, particularly against dark clothing. They can be especially problematic in seated groups, where at first glance you might think there are more hands than there should be.

One rule of thumb is to either show all of the hand or none of it. Don’t allow half a hand or a few fingers to show. Hide as many hands as you can behind flowers, hats, or other people. For men, have them put their hands in their pockets or “hitch” their thumb outside the pocket, which forms a nice triangle shape in the bent arm and gives recognition to the viewer that the hand is in pocket. For women, try to hide their hands in their laps or with others in the group.

Be aware of these potentially distracting elements and look for them as part of your visual inspection of the frame before you make the exposure.

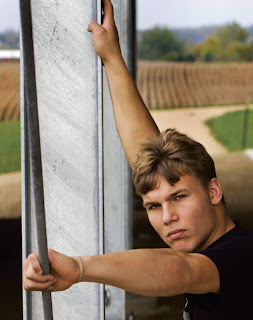

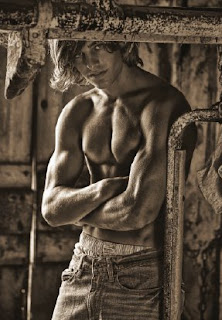

Hands in Standing Poses. When the subject is standing for a three-quarter- or full-length portrait, the hands become a real problem. If you are photographing a man, folding the arms across his chest produces a good, strong pose. Remember, however, to have the man turn his hands slightly, so the edge of the hand is more prominent than the top. In such a pose, have him lightly grasp his biceps—but not too hard or it will look like he is cold and trying to keep warm. Also, remember to instruct the man to bring his folded arms out from his body a little bit. This slims down the arms, which would otherwise be flattened against his body and appear larger. Remember to separate the fingers slightly.

With a standing woman, one hand on a hip and the other at her side is a good standard pose. Don’t let the free hand dangle, but rather have her twist the hand so that the edge shows to the camera. Always create a break in the wrist for a more dynamic line.

*excerpted from The Best of Portrait Photography, 2nd Edition.

BUY THIS BOOK FROM AMAZON