Today's post comes from the book Existing Light: Techniques for Wedding and Portrait Photographers by Bill Hurter. It is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.

Today's post comes from the book Existing Light: Techniques for Wedding and Portrait Photographers by Bill Hurter. It is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.Barebulb Fill. One of the most frequently used handheld flash units is the barebulb flash, which acts more like a large point source light than a small portable flash. Barebulb units produce a sharp, sparkly light, that is too harsh for almost every type of photography except outdoor portraits. Because the light falloff is less than with other handheld units, however, barebulb is an ideal source of fill light—either for backlit subjects or when a little punch of light is needed on sunlit subjects photographed early in the morning or at sunset when the sun is low in the sky. Barebulb units are predominantly manual flash units, so you must adjust their intensity by changing the flash-to-subject distance or by adjusting the flash output level. But whatever control you choose, the trick is not to overpower the daylight.

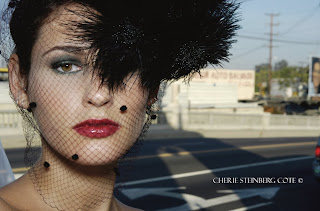

Cherie Steinberg Coté made this wonderful fashion portrait of a bride in a black veil on a downtown Los Angeles bridge. Her main lighting was matrix balanced flash with a Nikon D70 and SB-80 DX flash.

Cherie Steinberg Coté made this wonderful fashion portrait of a bride in a black veil on a downtown Los Angeles bridge. Her main lighting was matrix balanced flash with a Nikon D70 and SB-80 DX flash. Softbox Fill. Some photographers like to soften their fill-flash. Robert Love, for example, uses a Lumedyne strobe in a 24-inch softbox, which he triggers with a radio remote control. He often uses this at a 45-degree angle to his subjects (particularly for small groups) to create a modeled fill-in. For larger groups, he uses the softbox next to the camera for more even coverage.

To measure and set the light output for a fill-in flash situation, begin by metering the scene. It is best to use a handheld incident meter with the hemisphere pointed at the camera from the subject position. In this hypothetical example, let’s imagine that the metered exposure is 1/15 second at f/8. Now, with a flashmeter, meter the flash only. Your goal is for the output to be one stop less than the ambient exposure, so adjust the flash output or flash-to-subject distance until your flash reading is f/5.6, and set the camera to 1/15 second at f/8. At this point, if shooting digitally, it’s a good idea to take test shot.

Anthony Cava had this family pose under the tree, which blocked the overhead nature of the open shade. He then used flash-fill to add some sparkle to the faces.

Anthony Cava had this family pose under the tree, which blocked the overhead nature of the open shade. He then used flash-fill to add some sparkle to the faces. On-Camera Flash Fill.

Other photographers prefer to use on-camera TTL flash. Many of these systems feature a mode that will instantly adjust the flash output to the ambient-light exposure for balanced fill-flash. Many such systems also offer flash-output compensation that allows you to dial in full or fractional-stop output changes for the desired ratio of ambient-to-fill illumination. They are marvelous systems and, more importantly, they are reliable and predictable. Some of these systems also allow you to remove the flash from the camera with a TTL remote cord, increasing the range of effects you can produce.

Joe Buissink created this lovely and unique outdoor portrait of a barefoot bride sitting against a flowered wall. Joe used flash fill to get some twinkle in her eyes and added a canvas-effect to the image in post-production.

Joe Buissink created this lovely and unique outdoor portrait of a barefoot bride sitting against a flowered wall. Joe used flash fill to get some twinkle in her eyes and added a canvas-effect to the image in post-production. Flash Key Techniques

While location portraiture often calls for the existing light to function as the key light, there are some cases where the existing light is not ideal for this purpose. In these circumstances, you may wish to overpower the existing light and use flash as your key-light source.

Modern TTL-metered flash is the best way to set the ratio between existing light and bounce flash. Here, Dennis Orchard captured window light, incandescent room light, and bounce flash in a single exposure. The bounce flash was fired simply to open up the shadow side of the girl’s face and it is quite minimal.

Modern TTL-metered flash is the best way to set the ratio between existing light and bounce flash. Here, Dennis Orchard captured window light, incandescent room light, and bounce flash in a single exposure. The bounce flash was fired simply to open up the shadow side of the girl’s face and it is quite minimal. When adding flash as the key light, it is important to remember that you are balancing two light sources in one scene. The ambient-light exposure will dictate the exposure on the background and the subjects. The flash exposure affects only the subjects. Essentially, you are “dragging the shutter”—meaning that you are setting the camera to a shutter speed slower than the X-sync

speed (the fastest speed at which you can fire the camera with a strobe attached). The shutter remains open after the flash fires, allowing the ambient light to properly expose the background. Understanding this concept is the essence of flash-fill.

When using the flash-key technique, it is best if the flash can be removed from the camera and positioned above and to one side of the subject. This will more closely imitate nature’s light, which always comes from above and never head-on. Moving the flash to the side will improve the modeling qualities of the light and show more roundness in the face. It is also unwise to override the ambient light exposure by more than two f-stops. This will cause a spotlight

effect and render the background so dark that the portrait may appear to have been shot at night.

Saturating Backgrounds. If the light is dropping or the sky is brilliant in the scene and you want to shoot for optimal color saturation in the background, you can overpower the daylight with flash. Returning to the hypothetical situation where the daylight exposure is 1/15 second at f/8, you would now adjust your flash output so your flashmeter reading is f/11, a stop more powerful than the daylight. Then, you would set your camera to 1/15 second at f/11. The flash is now the key light and the daylight is the fill light. The problem with this is that you will get a separate set of shadows from the flash. This can be acceptable, since there aren’t really any shadows from twilight, but keep it in mind that it is one of the side effects.

Knowing the effect of backgrounds on exposure meters is crucial for a scene like this. Anthony Cava, a photographer well known for his fine portraits, shot this image as a commercial portrait for a clothing-design catalog. He metered the available light, decided to underexpose his background by almost a full f-stop, and fired an umbrella-mounted studio flash to provide brilliance and facial modeling. The light was positioned above and to the right of the model, creating a “loop” like pattern. No fill was used.

Knowing the effect of backgrounds on exposure meters is crucial for a scene like this. Anthony Cava, a photographer well known for his fine portraits, shot this image as a commercial portrait for a clothing-design catalog. He metered the available light, decided to underexpose his background by almost a full f-stop, and fired an umbrella-mounted studio flash to provide brilliance and facial modeling. The light was positioned above and to the right of the model, creating a “loop” like pattern. No fill was used. When using this technique to photograph more than one person, remember that electronic flash falls off in intensity rather quickly. As a result, you must be sure to take your meter readings from the center and—to be safe—from either end of the subject area. With a small group of three or four people you can get away with moving the strobe away from the camera to get better modeling—but not with larger groups; the falloff is too great. You can, however, add a second flash of equal intensity and distance on the opposite side of the camera to help widen the light. If using two light sources, be sure to measure both flashes simultaneously for an accurate reading.

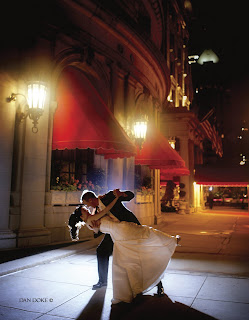

As you look at this photograph by Dan Doke, you might think the hotel’s outdoor lighting was very, very bright to create such sharp-edged shadows. Not so. The tungsten lighting is window dressing. The lighting pattern came from a hot (undiffused) strobe positioned behind the couple on a light stand. A diffused fill strobe at the camera position was used to create frontal detail in the image.

As you look at this photograph by Dan Doke, you might think the hotel’s outdoor lighting was very, very bright to create such sharp-edged shadows. Not so. The tungsten lighting is window dressing. The lighting pattern came from a hot (undiffused) strobe positioned behind the couple on a light stand. A diffused fill strobe at the camera position was used to create frontal detail in the image.

No comments:

Post a Comment