Today's post comes from the book

Jeff Smith's Studio Flash Photography: Techniques for Digital Portrait Photographers by Jeff Smith. It is available from

Amazon.com and other fine retailers.

Educators often talk about the quality of light that is produced by a light or light and modifier. I always thought this was confusing, as the term “quality” can also be used to refer to something that is a high quality—or better than others. Light has no quality, only quantity (the intensity or amount of light), but it does have characteristics—and it is these characteristics that are being referred to when a photographer says that a certain light or modifier was used to create a “quality” of light that was well suited to a subject.

In the studio, I have used everything from a spotlight to a cheap umbrella to light my clients’ portraits. Working outdoors, I have used soft light from the open sky as well as direct sunlight to produce the look I wanted. No single light source had a better quality than another. They all worked beautifully for the portrait I wanted to create. However, each source did have different characteristics.

When you conceptualize your portrait, you’ll need to decide whether you want a hard or soft lighting effect. Once you’ve made that decision, you’ll need to choose a main light source that produces light with the characteristics you are after. Let’s take a closer look at soft light and hard light so you can learn to identify and create the right lighting for the kind of portrait you want to shoot.

Soft/Diffused Light. Light is called “soft” or “diffuse” when there is a gradual transition from the highlight area of the image to the darkest shadow. In portraiture, soft light can diminish the appearance of harsh lines and wrinkles. It also produces less shine on the subject’s face than hard light will. The majority of traditional portraits are made with soft light. It is the most flattering light for portraiture and is more forgiving of poorly placed light sources. When I was a new photographer, I thought I should use the softest light possible. I was wrong. With a main light source that is too soft, the light lacks directionality and contrast, and the final image looks flat. It lacks the “pop” that you want in professional images.

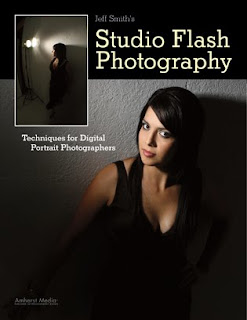

Soft lighting is the most flattering option for most portraits. As you can see in this trio of images from a single session (left and facing page), it can be used to create an array of great, salable images.

There are many modifiers available that will allow you to create the degree of softness you desire in your portrait. For studio and indoor location portraiture, most photographers use softboxes as a main light source. There are a wide variety of softboxes available on the market—from extra small to extra large or long but narrow. They are also available in various shapes. Some softboxes have a single layer of diffusion, and others have double diffusion. There are many variables that affect the characteristics of the light. Let’s take a look at how changing some of the variables will affect the look you’re after.

In general, a larger light source provides softer light than a smaller source. However, moving a large source farther from the subject makes it smaller relative to the subject. Therefore, when a large softbox is used close to the subject, it will emit a much softer light than it will when it is moved to 10 feet. (This is due to a shift in its size relative to the subject.) Therefore, if you are new to the profession and can afford only one softbox, you should realize that changing the light-to-subject distance will change the effect of the light on your subject.

The light-to-subject distance affects the look of the lighting in the image. The closer the light is placed to the subject, the softer the light.

There are other ways that you can manipulate your softbox to make its light a little softer or harder. If you are using a softbox with the flash head facing the subject, the light will be harder than it would be if you aimed the flash head at the back of the box, as the light would bounce off of the back of the box before passing through the diffusion panel. Also, directing the light through a single diffusion panel would produce a less diffuse light than you could create by adding the second diffusion panel that most softboxes come with. Also, with everything else being equal, a softbox with a silver interior will produce a light that is harder than a softbox with a white interior.

If the light from your softbox is too hard, you can create a softer lighting effect by using just the light from the edge of the softbox, rather than the harder, more direct beam of light emitted by the full front panel of the modifier. This technique is called feathering. I tend to select softboxes that produce more contrast than I typically want and feather the light to soften it. Feathering is a great technique that allows you to create workable light from sources that would not otherwise be usable.

I like to use a softbox with a silver lining and a thinner front diffusion panel (thicker material diffuses the light more, making it softer). This fits my style of photography and my clients’ tastes. The majority of my clients are high school seniors, and they like portraits that have more contrast and a higher color saturation. If you are using a softbox like mine but want more contrast, you can glue mylar or aluminum foil to the interior of the box. If your light is too contrasty for your tastes, you can add an inner diffusion material or replace the outer diffuser with a thicker fabric.

Hard/Directional Light. Hard light is characterized by hard, sharp shadows and high contrast. There is a quick transition from highlight to shadow. As I mentioned earlier, soft light is the choice of most portrait photographers. However, hard light, when carefully controlled, can be used to create dramatic portraits. The Hollywood photographers used hard light to create their classic, high-contrast black & white portraits.

Like modifiers designed to diffuse light, light attachments that create harder, more directional light have subtle variation in design and functionality, but all produce harder light than a softbox. A flash unit fitted with a parabolic (metal) reflector is the tool of choice as a main light source for most traditional portraits. These reflectors come in a variety of shapes and sizes as well as different interior finishes. There are a great number of accessories that can be attached to the parabolic reflectors to allow enhanced control over the light (snoots, grids, etc.). You can also modify your parabolics by changing the finish of the interior or putting diffusion material over the end of the reflector.

The effects produced by window light will vary depending on the direction the window faces, the time of day, and the type of glass in the window. Window treatments can further modify the light that strikes your subject.

When used correctly, parabolic reflectors will help you re-create that old Hollywood look. The best part of parabolic light is the amount of control it offers. When you can add light precisely where you want it, you can create a dramatic portrait.

A hard light setup and final image.

Today's post comes from the book Studio Lighting Unplugged: Small Flash Techniques for Digital Photographers by Rod & Robin Deutschmann. It is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.

Today's post comes from the book Studio Lighting Unplugged: Small Flash Techniques for Digital Photographers by Rod & Robin Deutschmann. It is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.