Today's post comes from the book Lighting and Posing Techniques for Photographing Women by Norman Phillips. In this book Phillips profiles 15 of the leading professional photographers working today to find out what techniques they use when photographing women. This book is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.

Today's post comes from the book Lighting and Posing Techniques for Photographing Women by Norman Phillips. In this book Phillips profiles 15 of the leading professional photographers working today to find out what techniques they use when photographing women. This book is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.Klarke is essentially a photojournalist, and her style is innovative and contemporary. The images in this chapter challenge many of the norms, but Klarke makes no apologies if her images shock the purists. It is all about capturing the moment. Her assignments are wide ranging; Klarke shoots corporate, PR, travel, fashion, and wedding images.

The first image is the result of cross processing color film. The provocative pose shows a lot of attitude. Posing the subject in profile and having her turn her head toward the camera will always provide interesting expressions with a little encouragement. To complete the pose, the subject positioned her fingers on the far side of her hat. The use of a black background made for a striking image.

A 48-inch softbox was placed slightly to the left of the camera for a flat lighting effect. Two large reflectors, one each side of the subject, provided additional definition and modeling. See diagram above.

In the photo above, the subject rested her elbows on a railing to create a relaxed composition. Klarke allowed her model to be comfortable and did not tweak the position of her arms and hand, so the resulting portrait has a casual look.

Note that the subject was turned slightly away from the camera, with the lens positioned slightly above her forehead. The angle of view caused her to raise her eyes to the camera with a quizzical expression.

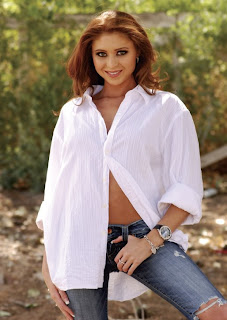

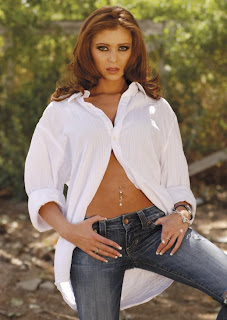

Strong sunlight from camera left was the primarylight source for this image. Flash was used to camera right to eliminate deep eye sockets and harsh shadows. The flat lighting, which is used often in glamour portraits, eliminated almost all the shadows and skin imperfections.

In this photo, Klarke had her subject shake her hair around to provide a natural and spontaneous pose and one that is likely to be attractive for the younger subject or fashion-conscious client. It is very effective when the subject has long, cascading hair. This subject had hair just long enough to make it work. We see this technique used on TV advertising hair products.

The main light was a small softbox placed to camera left and a little higher than her head. A domed reflector was placed below the subject’s face. A background light was used to create a slight haloed effect. See diagram above.

The above photo is another image that has the glamour treatment. The relatively static pose has impact due to the use of the red metallic dress. The subject’s head was slightly tipped to our right, breaking the vertical line of her torso. The position of her arms is one we frequently see, with matching lines created by the arms. The impression could be dramatically changed with her head tipped a little to our left. Another change that would create a different impression would be to have her extend her elbow toward her right knee.

A standard high-key background was used and a light was placed at each side of the camera to create the flat, glamour-style lighting.This next is a provocative image with sex appeal. The subject is attired in black lingerie, challenging us to respond to her presentation. For those interested in boudoir and glamour photography this is a good starting pose. The placement of her hand on her right hip is suggestive, and the raised knee created an attractive, boldly feminine impression. The raised knee also reduced the view of the black top, which provided another feminine element to the composition.

The lighting was mainly from a window to our right and her face was lit with a tungsten spot from a low angle to our left. See diagram below. The high-key set elements, black garments, and black props produced a dynamic fashion image with a glamour edge.

In the next photo, the subject was positioned in a casual leaning pose against a window, which created a high-key background and also eliminated a lot of detail in her hair. The front of the image was illuminated with a little flash and a reflector. The facial rendering is different from any we have so far seen and is in some ways reminiscent of what we see in everyday lighting situations.

Teenaged subjects often prefer a passive, almost disinterested expression as shown here. To bring another type of client to our studio it is a good idea to show some different impressions such as this, a portrait not unlike those we see in the windows of hair and beauty salons.

The pose shown below is almost a conventional three-quarter face. However, it was shot from a lower angle than we would expect to see. This caused the subject to look a little downward at the camera, thereby evoking an interesting expression. The slight tilt of her head to our right is what makes this portrait work so well.

The subject was photographed against a high-key background. The primary light for the image came from a skylight. Fill flash was used from the left, and an array of silver reflectors was used to open up all the shadow areas for a flat-lighting glamour style look.

In these images Klarke has challenged our conventional concepts in both posing and lighting and shown that there is a lighting style for all purposes and needs, providing we want to explore different techniques.

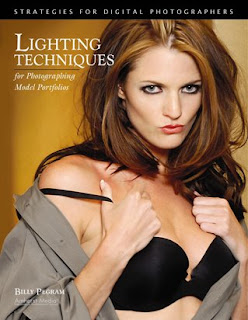

AVAILABLE FROM AMAZON

*excerpted from the book Lighting and Posing Techniques for Photographing Women