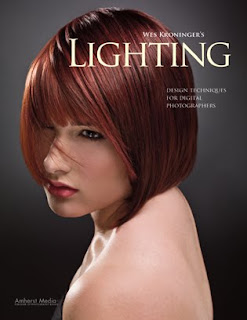

Today's post comes from the book Wes Kroninger's Lighting: Design Techniques for Digital Photographers by Wes Kroninger. For this post we are featuring three of his many lighting designs from the book. In this book Kroninger showcases a number of his remarkable images and breaks them down into how they were setup and what equipment was used to achieve the final result, often times including valuable tips about that shot. Each shot is accompanied by multiple diagrams. This book is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.

Today's post comes from the book Wes Kroninger's Lighting: Design Techniques for Digital Photographers by Wes Kroninger. For this post we are featuring three of his many lighting designs from the book. In this book Kroninger showcases a number of his remarkable images and breaks them down into how they were setup and what equipment was used to achieve the final result, often times including valuable tips about that shot. Each shot is accompanied by multiple diagrams. This book is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.The Scoop

This image is another example of the teamwork between performing and visual artists. It was captured in an abandoned warehouse where I had wanted to create a series of images for a long time. I visualized the juxtaposition of the beautiful lines of the dancers contrasted with the gritty texture of the old building. It took some investigation and a lot of phone calls to get access to the location, but the site proved to be perfect for the shoot.

Tech

There was no electricity, so battery-powered lights were used to create these images. One 4x6-foot softbox was used as the main light. A second bare-bulb strobe was placed off set to camera right to add some light to the darkened building. In this image, a third light was placed on the first floor pointing up through the hole in the floor at the bottom left of the image.

Tip

I did my research on which battery powered lights had the shortest flash duration, but I overlooked the fact that (to save on battery charge) most battery-powered strobe packs have little to no modeling light. As the sun set, this was a big problem while trying to focus. Fortunately, a friend had come to the set to shoot some video and happened to bring a generator with a hot light, which created just enough ambient light to focus.

The Scoop

When photographing actors for their promotional materials, it is a good idea to keep your lighting as simple as possible. Casting agents who are searching for acting talent like to see what a potential selection looks like without distractions or excessive embellishment. By keeping the lighting simple, you make the image a quick read of an actor’s facial features and overall appearance.

Tech

This is another example of how simple lighting can be when the right decisions are made for the right subject. Here, one medium softbox was used overhead. One reflector was used from below to add some upward fill. A digital “cross-processing” effect was used by selecting the tungsten white balance setting while using studio strobes; this created an overall cool blue tone to the image. Texture and grain were also applied for added effect.

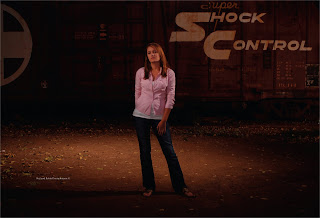

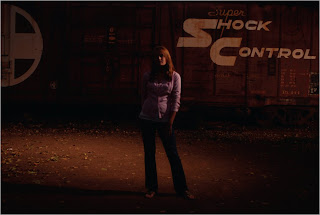

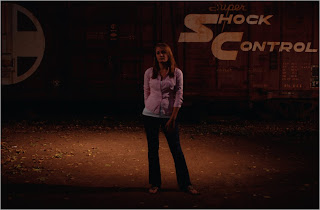

The Scoop

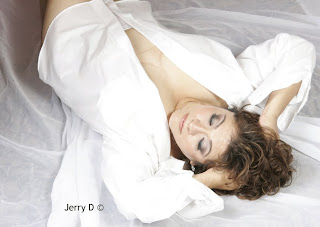

Some of the best experiences as a photographer come when collaborating with other artists. Working with dancers is no exception. They are so conscious of their movement and the position of their bodies in action that it guarantees a beautiful image.

Tech

To create this image, two 4x6-foot softboxes were used at corners of the set. To achieve a very short flash duration, I dialed the pack down to a low setting. I adjusted for this loss of illumination by increasing the ISO of my camera to 400. (I generally hesitate to go above 400, because I want to eliminate as much grain or digital noise from the image as possible.) The model was backlit with two gridded lights at the edge of the seamless paper, one on either side.

Tip

When I photograph dancers, I like to stop motion. I find it fascinating to see still frames, frozen in time, of movements that otherwise pass so quickly before our eyes. Certain equipment selections have to be made to achieve these results. Some lights have very fast flash duration (the flash tube itself stays illuminated for a short duration during each firing). This speed eliminates any streaking or blurring in the captured image— because, essentially, the light is doing the work of your shutter. Most strobe packs offer their shortest flash duration when at low power settings, then grow longer as the power is increased.