Today's post comes from the book Professional Portrait Photography: Techniques and Images from Master Photographers by Lou Jacobs Jr. This book is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers. In the book, Jacobs profiles 10 leading portrait photographers about their craft and their business. Here is an excerpt from his profile of photographer Chris Nelson.

Today's post comes from the book Professional Portrait Photography: Techniques and Images from Master Photographers by Lou Jacobs Jr. This book is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers. In the book, Jacobs profiles 10 leading portrait photographers about their craft and their business. Here is an excerpt from his profile of photographer Chris Nelson.

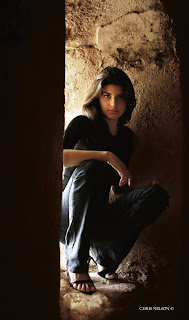

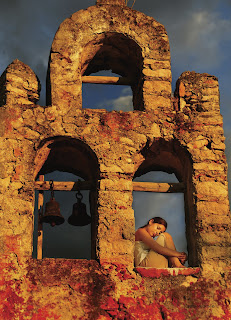

A former photojournalist and reporter, Chris used to supplement his income shooting weddings, advertising images, and senior portraits. In high school in the 1970s, he and his friends built a darkroom and shot for the school paper, yearbook, and sporting events. In 1991, he started a portraiture business now called Fall Creek Portrait Design in Fall Creek, WI. Since portraiture became his lifelong interest, Chris has earned Accolades of Photographic Mastery and Outstanding Photographic Achievement from WPPI, and is proud of winning WPPI’s senior portrait category in 2002 and 2004.

Describe your background.I studied at University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee and graduated with a BA in English with photojournalism and fine art photography as part of my studies. While still in college, I did photography and graphic design for the college magazine, and after graduation, I worked at several newspapers as a reporter and photographer. Since my background was not portraiture, I wanted to learn all I could about this new area, and joining WPPI and PPA were great avenues.

Who are your influences and mentors?When I caught Monte Zucker’s 1999 tour, and that of portrait artist Al Gilbert, I was blown away by their use of barebulb flash, as opposed to using softboxes, umbrellas, and reflectors. Those photographers had fluid posing styles that made subjects look really natural. I analyzed what they were doing and adopted some of their techniques so my work would look different from most other photographers’ portraits.

Don Blair and Michele Gauger influenced the foundations of my photographic style. Robert Lino and the late Dean Collins influenced my glamour style. While glamour photography comprises only about 20 percent of my studio’s business, that style influences much of my work. All my high school senior girls want to look like models, and seniors are 60 percent of my business.

Describe your studio.

Describe your studio.I worked out of my home studio during a three-year transition from photojournalism to portraiture. I continued to take assignments with the local newspaper and shot for Chippewa Valley Technical College, creating images of students for the school’s cutting-edge programs.

In 1994, I moved into my current building, an 1880s bank on the main street of Fall Creek, WI (population 1,250). After renting half the building, I bought the property in 1998 and began restoration. In 2004, I added a large window-lighted camera room, a new production room, and a second dressing room. The studio is now about 3,000 square feet. Though I have two camera rooms, I still do a lot of location work because my clients and I love the variety. Many photographers in the vicinity don’t leave their studios.

I have three employees, my daughter Erin, my son Tim, and Ashley who does a little of everything, except shooting. She specializes in Photoshop, retouching, and finishing images, does client consultations, and a good share of the sales work.

Erin is like Ashley’s understudy, with much the same aptitude for graphics software applications. She has a great eye for design and is in training for high school senior album layout. Tim is a high school junior who enjoys being second camera at weddings, doing mostly candids. We expect when he’s in college he can shoot weddings on his own.

How do you approach your sessions?The root of portraiture is the word portray. Photographers seek to visually portray their clients in artistic images that describe aspects of their lives or personalities. Before sessions I normally do a consultation where we get to know each other and exchange ideas; that helps keep us on track. How I approach getting what they want evolves through my style, coming from my consciousness and vision. If a casual observer can identify with and understand the meanings conveyed by an image, it’s a good, if not a fine, portrait.

How do you approach posing?I have favorite poses, but they have to fit the subject. A pose might look great for one person and awkward for another, so you have to analyze your subject. My job is to accentuate the good features and downplay or hide what we don’t want to show through lighting. I try to make a positive aspect of the subject’s appearance so dramatic and compelling that viewers don’t notice a negative. For example, I created a glamour portrait of a woman who had recently had a baby and hadn’t lost all of her belly. She said her husband loved her butt, so I posed her with it at about a 30-degree angle to the camera and had her twist at the waist and look over her shoulder. This hid her tummy, and we chose a high key background with a hint of pink, which blended with her outfit.

In the last few years, I’ve adopted a new posing style by letting people pose themselves. I have clients talk about themselves and I watch their body language. When they do something that looks good, I tell them and then light that pose so it looks natural. This saves the effort of trying to fit someone into a pose. For example, I told a senior girl to pose on a stool in front of a formal

background. Instead, she knelt on it, sitting on her hocks, a pose I’ve never seen before. I said she looked great. I turned the stool about 45 degrees away from the main light, and she turned to look at me. The picture was uniquely her.

What strategies do you employ to communicate with your subjects and elicit the desired expressions?I often describe the photo session as a stage performance where the part clients play is to talk about themselves. I reassure them, especially shy clients, that it’s my job to make them look good. “What’s the most important thing about a picture?” I’ll ask, and I get all kinds of answers. I’ll say, “The real answer is that you look great. The better I understand what you want, the better I can do this.”

In my orientation about posing, especially for women, I mention the ability to move body parts separately, face toward the light, and tip their head over their left shoulder. I’ll tell them, “Don’t move your upper body, but turn your hips away from me to the right.” I also tell people I don’t want them to smile all the time, that we need to capture a range of moods and expressions. I’ll suggest, “Point your chin toward me a little,” often getting a slightly bewildered look. Their cooperation shows they know I care what their images look like.

Shooting sequences is critical. If you get a good pose, quickly get different angles that really add variety to a sitting. Ask clients not to abandon a pose as soon as they hear the shutter click.

What type of backgrounds work best for you?When we expanded the building we left the exterior brick exposed. I add props such as an old antique radio and phonograph, or antique furniture. I prefer props you find by chance to those from photographic catalogs, though I do have some of those. I also own painted backdrops, both muslins and canvases.

When a contractor remodeled a house near my studio I was given great old columns, a couple of which now frame the Plexiglas block window I built. I covered the cracked paint of the columns with a light coat of turquoise paint that harmonizes with the earth tones. The columns are used as the center of a set with the Plexiglas window backlit using a tungsten lamp.

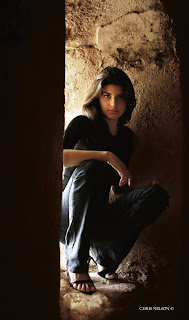

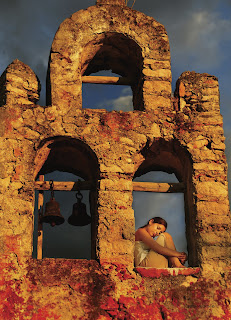

Do you conduct any location sessions?At least 60 percent of my sessions include an outdoor segment, which pleases seniors, couples, and families. We use one of our terrific locations like the rusty riveted steel and geometric trusses of an old railroad bridge. I work in natural light at a dozen or so spots near my studio, and I often augment with a strobe. The sun is a main light, the ambient light level is another, and my strobe or reflector is a third.

Where the sun is intense and there’s no shade or reflected light, I’ll use the sun as backlight with a portable strobe as a main light. If the ambient light level is f/5.6 at 1/250, I’ll set the strobe at f/5.6, which gives me an f/8 highlight or a 2:1 ratio. An f/11 separation light (the sun) gives the subject’s hair a beautiful highlight.

The junkyard is another favorite spot for seniors. I found it doing a senior session for the owner’s son, and I immediately made arrangements to shoot there often. I also use a rustic barn with peeling paint, a hayloft, and antique implements. Horses, goats, geese, turkeys, and ducks add to the atmosphere.

How do you promote your studio?One main advertising site is a mall kiosk where we have a 10x18-foot display at a key spot; it’s expensive but worth it. We rotate images often, and clients who appear in the display are flattered. Once a year, we sell the prints at 55 to 70 percent off list. Equally important is our web site, which keeps growing and is really quite a bargain. Do your best to keep your web site fresh. The more places you can reinforce your message, the better.

You are in a position where your photography can promote a lot of other businesses (or nonprofits) and end up photographing in the process of doing your job. This type of networking is huge and often doesn’t cost much. I make images available to hotels, limo companies, bars, hair salons, radio stations, and hospitals for nothing more than a photo credit. It’s surprising how much word of mouth you get as a result.

We also do as many as twenty different mailers a year, many of them smaller like our re-order and customer appreciation sale, plus the four we do yearly to our senior prospects. Always refer prospective clients to your web site, where you can put more detailed information. I also do radio advertising and trades for promotional events as well as giving sessions away to nonprofits and community organizations.

How important is a photographer’s personality to his or her success?Your personality and your ability to communicate with and understand your clients is critical. They will love you for making the effort. In addition, you need to decide what kind of image you want people to have of your studio. They need to understand what kind of photography you do. Image and branding is important, and you have to make the decisions noted above. Once you decide on the message, don’t ever water it down.

BUY THIS BOOK FROM AMAZON

BUY THIS BOOK FROM AMAZON

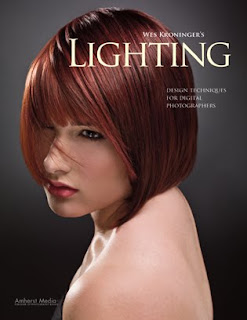

Today's post comes from the book Wes Kroninger's Lighting: Design Techniques for Digital Photographers by Wes Kroninger. For this post we are featuring three of his many lighting designs from the book. In this book Kroninger showcases a number of his remarkable images and breaks them down into how they were setup and what equipment was used to achieve the final result, often times including valuable tips about that shot. Each shot is accompanied by multiple diagrams. This book is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.

Today's post comes from the book Wes Kroninger's Lighting: Design Techniques for Digital Photographers by Wes Kroninger. For this post we are featuring three of his many lighting designs from the book. In this book Kroninger showcases a number of his remarkable images and breaks them down into how they were setup and what equipment was used to achieve the final result, often times including valuable tips about that shot. Each shot is accompanied by multiple diagrams. This book is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.