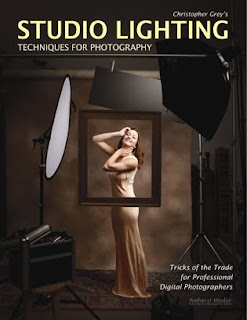

Today's post comes from the book Christopher Grey's Studio Lighting Techniques for Photography. This book is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.

Today's post comes from the book Christopher Grey's Studio Lighting Techniques for Photography. This book is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.One of our jobs as successful photographers is to identify and exploit trends, which frequently make themselves known through commercial advertising. Like many advertising shooters, I have a love/hate relationship with art directors, those ad agency folks who dream up the ads in the first place.While I hate it when they make what I might think are dumb creative decisions during a shoot, I love them because they are paid to dream up attention-getting visuals for typically mundane subjects (and for paying me handsomely to produce the images). Art directors are often responsible for trends, because when they see a successful image from another agency, they tend to use it as a point of departure. When enough art directors do this, a trend is born through “trickle-down creative,” eventually making its way through the entire industry as clients begin asking for the “look.”

I’ve been seeing more and more national advertisements shot with simulated sunlight—beautiful images with clearly defined shadows and small, specular highlights. Is this a trend? Probably. I think we’ll see this style continue for quite a while. Is it cool? Absolutely.

There are several ways to simulate sunlight, and simply going outside is not a viable option because you have no control over the situation. It’s simply impractical.

HMIs were created for the motion picture and video industries. They are continuous sources like traditional hot lights and are pricey to rent (usually only from cinema supply houses) and very expensive to buy. However, they produce a very convincing “sunlight.” Larger HMIs can illuminate entire city blocks.

If you use hot lights, you should use something with a focusable fresnel spot in order to keep the shadows sharp. Pay attention to the crispness of the shadow and also to the amount of fill you might need.

Far and away, the most practical lights are studio strobes. If you simply attach a small reflector, however, you may not get an authentic look, especially when lighting someone in a larger area. Light modified with a reflector will not spread out in all directions as sunlight does, nor will it create a correct shadow shape. I think it’s a good idea to tilt the strobe head to the 11:00 position, relative to the subject, so that the subject receives the full blast of the tube without any additional reflection from the strobe unit itself.

Deeper shadows can be achieved by adding a subtractive fill device, like a black bookend, to the shadow side of the image. There is a slight loss of bounced light against the background, which would not be as noticeable if the background were a darker color.

The next shot (left) would have appeared flat without the addition of a narrow strip light between the subject and the background. The strip light was angled carefully to avoid any spill onto the model or the towels. It was powered at 1/2 stop over the main light, as measured at the top of the frame, and allowed to fall off to give the image vertical depth, perhaps like a skylight. If I’d wished to keep it even, I’d have set the strip light vertically at camera left and feathered it evenly across the background.

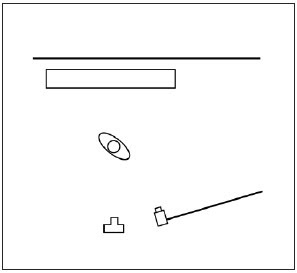

The barebulb strobe, placed above and just slightly to camera right, threw beautiful, even light on the model. The crisp shadow shows plenty of detail because the bulb sprayed light in all directions and it bounced around the room. The texture of the towels looks great because the small source created a small, sharp shadow on each fabric loop (image above and diagram below).

If you need to give the illusion of sunlight as an accent, take advantage of the barebulb’s ability to produce distinct shadows and mimic the shape of a window and direct light through it. I used a pair of black bookends to create this shape. The black absorbed a lot of the extra light before it could bounce around the room and possibly affect the exposure of the main light. The window light was powered to 1 stop over the main light, a medium softbox. Even though that light was so much brighter than the main light, it brightened the dark wall, just not enough to overexpose it.

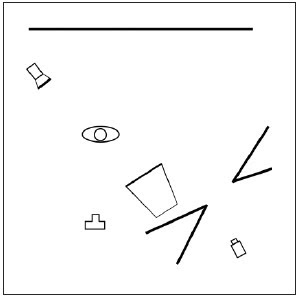

I wanted to give the image above a look of stage light, which is often perceived as a little hot, so I powered both the hair light and the background accent light to 2/3 stop brighter than the main light (image above and diagram below).

Creating a window with panes is really easy. The image shown on the facing page, shot for a magazine cover, uses an additional technique that you might find interesting. The basic window shape was made as before, by sectioning off a piece of the studio with black bookends. After moving two light stands into position behind the bookends (so their shadows wouldn’t show), I used clamps to attach a small wooden plank between them. Leaning a wider plank vertically against the crossbeam completed the illusion.

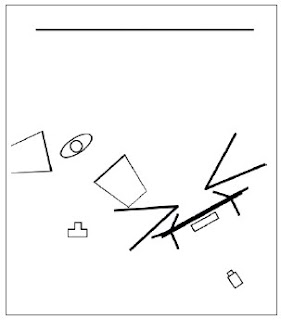

The main light, a 3x4-foot medium softbox, was aimed at the model at the same angle as the simulated sun. Another softbox was placed at camera left, very close and powered 2 stops less than the main light—just enough to open up the shadows. The modeling lamps for the main light and the window light were turned off, but the modeling lamp for the side light was left on. My shutter speed was 1.5 seconds. The strobes fired at the start of the handheld exposure, and the additional open shutter time created the warm fill and slight motion blur (diagram above and image below).

BUY THIS BOOK FROM AMAZON

No comments:

Post a Comment