Today's post comes from the book Simple Lighting Techniques for Portrait Photographers by Bill Hurter. It is available at Amazon.com and other fine retailers.

Today's post comes from the book Simple Lighting Techniques for Portrait Photographers by Bill Hurter. It is available at Amazon.com and other fine retailers.Key Light

The function of the key is to shape the subject. It should draw attention to the front plane (the “mask”) of the face. Where you place the key light will determine how the subject is rendered. You can create smoothness on the subject’s face by placing the light near the camera and close to the camera/subject axis, or you can emphasize texture and shape by skimming the light across the subject from the side.

The key light should be a high-intensity light. If using diffusion, such as an umbrella or softbox, the assembly should be supported on a sturdy stand or boom arm to prevent it from tipping over. If undiffused, the key light should have barn doors affixed to control the light and prevent lens flare.

Here is an example of a really big key light. Charles Maring often uses a 7-foot Profoto reflector as a single key light with no fill. In the close-up of the senior’s eyes (below), you can see the differentiated interior of the round reflector, with varying degrees of reflectivity mirrored in her eyes. A single strobe fired into this reflector created this amazingly soft wraparound lighting. The exposure was at f/16 to keep all the girl’s hair in focus.

In most cases, the key light is placed above and to the side of the face so that it illuminates both eye sockets and creates a shadow on the side of the nose. The nose shadow should not cross over onto the cheek, nor should it go down into the lip area.

When the face is turned for posing, the key light must also be moved to maintain the lighting pattern. For example, the light will be positioned at approximately a 45-degree angle to the camera when photographing the full face of a subject. However, when the subject turns to show the camera a two-thirds facial view, the key light will need to shift with the camera to maintain the same lighting pattern as in the first shot.

In this beautiful portrait by Tim Schooler, the large key light, a soft box, was placed to camera right. Because the light was so diffused, Tim did not use a fill light or reflector. Instead, he positioned the light to optimize its coverage from the subject’s feet to her hair. In addition, he used a fairly strong hair light (a strip light) above the model to amply light her hair. The size and proximity of the subject to the key light make for elegant and very soft lighting.

Normally, you will want to position the main light close to your subject without it appearing in the frame. A good working distance for your key light, depending on your room dimensions, is eight to twelve feet. Sometimes, however, you will not be able to get the skin to “pop,” regardless of how many slight adjustments you make to the key light. This probably means that your light is too close to the subject. Move the light back or feather it.

To get an accurate exposure reading, position a handheld exposure meter directly in front of the subject’s face and point it toward the light source. Make a few exposures and verify the exposure on the camera’s LCD. If your system allows you to check a histogram of the exposure, check it to make sure you have a full range of highlight and shadow detail.

Fill Light.

Just as the key light defines the lighting, the fill light augments it, controlling the lightness or darkness of the shadows created by the key light. Because it does not create visible shadows, the fill light is defined as a secondary light source.

The fill light should always be diffused. If it is equipped with a simple diffuser, a piece of frosted plastic or acetate in a screen or frame that mounts over the parabolic reflector, it should also have barn doors attached. If using a more diffused light source, such as an umbrella or softbox, be sure that you are not “spilling” light into unwanted areas of the scene, such as the background. As with all lights, these units can be feathered, aiming the core of light away from the subject and just using the edge of the beam of light.

Chris Nelson photographed this young lady with a softbox as a main light. He used a silvered reflector for fill, a strip light for the hair light, and a background light. The softbox and strip light were set to the same output level; the background light was set to a stop less. The camera angle was about a foot over the subject using a telephoto lens. He used a fan on low to give her hair some fill and lift. Chris says of this pose, “Never use it unless your subject has long sleeves on, and don’t use it if the arms are abnormally large or well developed.”

The best place for the fill source is as close as possible to the camera-to-subject axis. All lights, no matter where they are or how big, create shadows. By placing the fill light as near the camera as possible, all the shadows that are created by that light are cast behind the subject and are less visible to the camera.

When placing the fill light, keep a watch out for unwanted highlights. If the fill light is too close to the subject, it often produces its own set of specular highlights, which show up in the shadow area of the face and make the skin appear oily. If this is the case, move the camera and light back slightly, or move the fill light laterally away from the camera slightly. You might also try feathering the fill light in toward the camera a bit. This method of limiting the fill light is preferable to closing down the barn doors or lowering its intensity.

The fill light can also create multiple catchlights in the subject’s eyes. These are small specular highlights in the iris. The effect of two catchlights (one from the key light, one from the fill light) is to give the subject a vacant stare or directionless gaze. This second set of catchlights is usually removed in retouching.

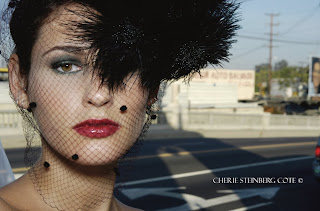

In this beautiful glamour portrait by Tim Schooler, the key light comes from behind the subject a little to camera right. You can determine this because the right side of her face and nose are highlighted. The fill light, which is close to the same intensity as the key light, comes fromcamera left and fills the shadow side of the model’s face. Additional fill is achieved by the white crepe material, which is reflecting light everywhere within the scene. You will notice that even though the lights are fairly even in intensity, the key light still provides direction and bias.

In simplified lighting patterns, the source of the fill light may not be a light at all but a reflector that bounces light back onto the subject. This means of fill-in has become quite popular in all forms of photography. The reflectors available today are capable of reflecting any percentage of light back on to the subject, from close to complete reflectance with various mirrored or Mylar-covered reflectors to a very small percentage of light with other types. Reflectors can also be adjusted almost infinitely just by finessing the angle at which they are reflecting the fill light.

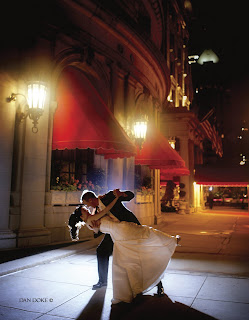

Master photographer Drake Buseth often uses the outdoors as his studio. Even so, a key light and fill light are still called for. Here, a large softbox was used over the lens as the key light and a large reflector was angled up from beneath the camera as a fill-in source. The effect produces a gentle lighting ratio.

THE PERFECT FILL

If it were a perfect world, fill light would be shadowless, large, and even—encompassing every part of the subject from top to bottom and left to right. The fill light would be soft and forgiving and variable. And it would complement any type of key lighting introduced.

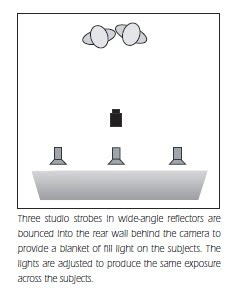

Just such an effect can be created using strobe heads in wide-angle reflectors bounced into a white or neutral gray wall, or a flat behind the camera (the surface must be neutral to ensure no color cast is introduced). Usually, the first two lights are placed to either side of the camera, then the third is placed over the camera and aimed high off the flat or the wall/ceiling intersection.

These lights are placed close to the wall and ceiling, creating a wall of soft light. These fill lights are then balanced to produce an identical output across the subject. The key light, which may be placed to the side or above the subject, will be equal to or more intense than the fill source, creating a ratio between the fill and key lights.

A variation on this setup is to rig a large white flat over and behind the camera. Two or three strobe heads can then be bounced into the flat for the same effect as described above. Some of the light is bounced off the flat and onto the ceiling, providing a very large envelope of soft light.

A variation on this setup is to rig a large white flat over and behind the camera. Two or three strobe heads can then be bounced into the flat for the same effect as described above. Some of the light is bounced off the flat and onto the ceiling, providing a very large envelope of soft light.BUY THIS BOOK FROM AMAZON